THE BIRTH OF SONNING CUTTING

Whilst the story of Woodley and its association with Sonning Cutting should in theory only extend from Lands End in the east, to Shepherds House in the west, as they are the respective district boundaries: Nevertheless, as the great works extended for a further quarter of a mile to the west, common sense dictates that these should be included where relevant.

Sonning Hill is the name given to the northern side of the high land mass which rises from the flat Kennet plain, approximately two miles from Reading .Extending both eastwards, and southwards through Earley a further mile and a half, this high ground was always going to pose a problem for any engineers planning a direct railway route to Reading from London.

Whilst schemes to build a railway between Bristol and Reading had come and gone, our story begins in 1834, as reported in the 16th March edition of the Berkshire Chronicle:

“THE GREAT WESTERN BILL

In conjunction with the document, MR. C RUSSELL presented a petition to Parliament from the inhabitants of Reading, which set forth the advantages that would result from the construction of the proposed GREAT WESTERN RAILROAD. With 800 signatures in favour, it had been adopted at a public meeting, although not everyone was in agreement as Mr. PALMER who opposed the motion was quoted as saying, “those in favour of it about Reading and other places had not a foot of land”.”

Nevertheless, despite organised opposition, the Bill received the Royal Assent on 31stAugust 1835 and so the Great Western Railway was incorporated. Within days of the Royal Assent Brunel and his assistant Townsend were busily engaged in setting out the two sections of the line, namely from Bristol eastwards, and westwards from London to Reading. As for our narrative it involves CONTRACT No. 8.1: the formation of that portion of the railway commencing at the termination of contract 7.1. (Twyford) – extending to Caversham Road at Reading; in doing so requiring the building of a tunnel through Sonning Hill. Shortly after Brunel had a change of plan, dropping the tunnel for a deviation slightly to the south.

Brunel had decided at the outset to maintain his ‘billiard table’ gradient at 1: 1,320, hence the need for a very deep cutting of between twenty and sixty feet. Excavating through sand, clay and deep water from numerous springs that were encountered, at its deepest part it required the removal of 7,800 yards of spoil for every one foot forward in distance.

By the beginning of March1837 the formation was proceeding at great pace, having reached the point where the railway is carried under the London Road. At the western flank of the hill, where a high embankment commenced, an incline plane assisted the transit of wagons, which descended with great velocity, laden with soil, at the same time that they raised in a contrary direction the empty ones by the medium of a huge cable roller. Unfortunately for Brunel, it was at this same time that the excavators left work, declining the lower amount of wages offered by the contractor William Ranger who presumably was running into financial difficulties.

By the turn of 1838 things started to go seriously wrong with the rate of progress in the excavation of the cutting, as works fell further and further behind schedule. As for William Ranger, improvement in his rate of progress was never to materialise, as things got steadily worse. Finally in August 1838 the company ran out of patience and dismissed him. With his former workers now out of work, there was a very wary populace in the nearby market town as they witnessed numerous navies loitering and inconveniencing the general public.

Strangely, on 30thAugust, more than a year after the substitution of a cutting had been announced, and an Act for the deviation obtained, the decision was taken for a bridge to be constructed to carry the Bath Road over the deep cutting.

On 8thOctober 1838 the directors visited the works to find a mixed bag of progress. Whilst the eastern end was progressing well they found that workmen had struck at the western end. As for the contractor, Knowles, he was threatened with dismissal unless things were placed in a more satisfactory condition. As it turned out the threat was to no avail, leading to his being sacked a couple of weeks later, with the work resumed under the Company’s engineers.

In February 1839 the directors noted that 1,220 men and 196 horses were employed on the cutting, with two locomotives recently purchased by the company to give the required assistance. Whilst there was still 700,000 cubic yards of earth to remove, it was noted that the workforce had exceeded 23,000 cubic yards in one week. Furthermore, when the locomotive power entered into service it was estimated that the weekly excavation figures would be increased to 35,000 cubic yards.

Unfortunately the constant seven days a week working did not please all of the local populace for in March the Berkshire Chroniclecarried a long letter complaining of: – “SUNDAY WORK ON THE RAILROAD.”

It was inevitable that there would be disputes among a workforce of 1220 men. In April 1839 George Greenaway was killed in a fight outside the Bull and Chequers pub by a fellow railway worker John Siddall. According to the newspaper report, Siddall was egged on by 30 fellow workers. The court gave him a sentence of a fine and a short stay in prison.

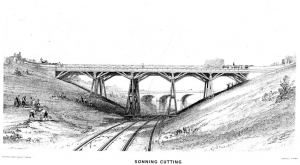

Image from John Bourne’s book: Great Western Railway 1846, courtesy of Reading Borough Libraries

Despite the company’s optimism that the permanent way would start being laid by the mid-summer of 1839, heavy excavation was in progress, with the resultant injuries and fatalities to match. One such incident occurred when a very large vein of hardened clay which had almost undergone a transformation into stone had been causing the excavation rate to be drastically reduced, for quite a considerable period of time; in doing so requiring the use of gun powder. On Tuesday morning, 2ndJuly, a small barrel of the explosive was brought to the shaft being worked on, when for whatever reason it exploded. Five men, one of whom (and the trolley he was sitting on) being lifted and thrown a considerable distance by the ferocious blast. Two of the individuals, their sight temporarily lost, were taken to the newly opened Royal Berkshire Hospital. As for the remainder, despite serious lacerations they were taken to their lodgings.

Coincidental with the latter accident, the directors of the Great Western Railway were only too aware of the high number of casualties taking place along the course of the works. In recompense they decided to give a donation of 100 guineas (£105), added to which a subscription of ten guineas to the local hospital.

The latter accident was just one example of many that occurred during the construction of the cutting. The Royal Berkshire Hospital had opened for accident cases on Tuesday 28thMay and within that first week there were two admissions, both resulting from accidents occurring in the cutting. The very first patient was a mere fifteen year old lad, George Earley, who had sustained a compound fracture of the humerus. Amputation at the shoulder was decided upon, which Mr. Young, one of three surgeons elected to perform.

Operations were extremely rare occurrences in those days, but fortunately for young George, all had been successful. It was to be a further nine weeks before he was discharged. The day following George’s operation, James Wetman was admitted with a fractured leg which resulted from a fall of earth. After the previous day’s work this was just the first of many casualties that the newly opened hospital had to contend with.

Come August, still the work continued unabated. An estimated 145,000 cubic yards still remained to be excavated and this arduous task was to take virtually the remainder of the year to complete. That mid-summer also witnessed the construction of two bridges across the cutting, both at the highest point. The already mentioned Bath Road Bridge, which still stands today, was 60ft high, constructed of brick, with three arches, with the twin tracks taking the larger centre one.

The second example was located a couple of hundred yards to the east of the former example. For this Brunel chose timber, building it in the style he was later to adopt for numerous viaducts, particularly in the West Country. With a span of approximately 240ft, it had four tapering piers from which raking struts fanned out to support the deck above; in doing so reducing the effective distance of span. Whilst relatively cheap to construct, the bridge was to last until the quadrupling of the cutting in 1893 when it was replaced by the present-day lofty iron latticed structure.

Following a survey during the first weeks of 1840 the conclusion was that there was nothing to prevent the line being opened from Twyford to Reading. As for the track, it consisted of 62lbs bridge rails on longitudinal sleepers.

All was now ready for a number of trial runs to prove that it was safe for the commencement of the railway service. Daniel Gooch had the honour of taking a number of the directors and numerous other individuals down to Reading on 17thMarch. Things would never be the same again. As for the very first passenger train, this departed from Reading for London at 6.00 am on 30 March 1840, hauled once again by Firefly.

As would be expected with such a large excavation and the long high embankments either side, it would require a considerable period in time before everything would finally settle down. Inspections on a daily basis were still continuing within the cutting during December of the following year. Mr. Bertram, assistant engineer to the Great Western Railway no less, personally taking charge of the task. There had frequently been small slips, invariably caused by water building up below the surface. The remedy was to remove the spoil, drain the water and remake the contour.

THE CHRISTMAS EVE 1841 DISASTER

During the dark evening of Christmas Eve 1841, near to the high wooden bridge, a fairly small slip occurred which encroached over the nearside rail on the down line. At about the same time as the slip occurred the 4.40pm departure from Bishops Road (the original Paddington station) was heading west from Twyford. Described by driver, Thomas Reynolds, as a goods train, it in fact had three open carriages behind the tender and in these primitive vehicles were numerous passengers returning home for Christmas. Some were stonemasons who had been working on the Houses of Parliament. As the train passed Lands End, just to the east of the cutting, the guard, George Hanson, witnessed that the policemen (or” Bobby” – as signal men were in those days) had given the signal that the road ahead was clear and so, with the locomotive Heclaat the head, the train unsuspectingly entered the cutting. Sadly, within minutes the locomotive had hit the slip and come off the rails. The following open carriages then piled into the tender whilst being compressed by the wagons behind, leaving a picture of devastation to the observer.

Amongst the first to arrive on the scene was a local man Mr. Gosling. As he hurried down the side of the steep cutting his attention was drawn to the “groans, shrieks and yells, and the shattered timber rested upon and mixed with the dead and dying.” Immediately he found two men, “crushed or jammed in contrary directions, both dead.” Next he observed, on the south side of the line, three other persons lying under the remains of the forward truck, which had broken to pieces. The appearance of the mutilated remains he would never forget.

Next his attention was drawn, by her shrieks, to a woman in a kneeling posture begging to be extricated from a trunk that had fallen over her legs. Owing to the danger of removing the wheels of the carriage under which she was trapped, nothing could be done until the earth was properly shored up. It was to be nearly an hour before the unfortunate woman could be released from her acute suffering. A little further on were two men, both dead, and an eighth lying on the embankment. Meanwhile, as Mr. Gosling witnessed the tragedy surrounding him, two railwaymen were already running in either direction so as to intercept any trains which might be approaching.

Gathering his wits about him, Mr. Gosling sent for his horse and cart, with straw, for the conveyance of those still alive. Unbelievably as he did so, he and the other helpers were exposed to great incivility by a number of the company’s servants, being ordered off the line with threats of being taken into custody!

In total eighteen injured passengers were taken to the hospital, “… twelve of the unhappy sufferers were so materially injured, that their further removal was deemed to be dangerous, and they were, by the medical officers of the institution, admitted as patients.”

One of those admitted to the hospital was Richard Wooley, a 32 year-old stonemason. He had been found lying on the embankment with his head bleeding profusely. He was diagnosed as having extensive compound fractures of the skull, with a deep depression of the bone on the membranes of the brain. An operation was immediately considered necessary; the depression was elevated and the skull then pinned in numerous places. Such was his violent post operative state he required a straight-jacket until his death the following Wednesday. Richard was to become the fifth person to lose his life in the terrible accident.

In total three carriages behind the tender were wrecked, the rest of the train (which was composed of wagons) being apparently totally unscathed. Once the injured had been removed from the scene, an engine was brought up from Reading to facilitate the removal of the deceased.

At the inquest at Shepherds House, Brunel gave evidence at great length:

“I arrived at the spot where the accident occurred at about half-past eleven o’ clock. They had not yet removed the earth from the rail. I examined the site very carefully … I was surprised at so much mischief having been produced by the comparatively small quantity of gravel which had slipped. And I found some large stones which had slipped with the clay – being part of the bed of stone which lies a considerable height up the cutting – one of these stones, probably two feet square, appeared to have been on the rail just at the point where the engine left the line”.

The first inquest took place the next day. The Board of Trade and the Times reported it on Christmas Day. According to the law of the time, The Great Western was found guilty and was fined £1000. The money was to have been given to the lord of the manor, Robert Palmer of Holme Park, Sonning, to distribute to the injured and families of the dead. He never received any money, so the victims had no compensation. He was the same Robert Palmer who had objected to the building of the railway.

As a precaution, to prevent a recurrence of the Christmas Eve disaster, an increase in the number of watchmen in the cutting and its approaches was instigated. Whilst this move certainly served the interests of the travelling public, the same could not be said for the newly recruited staff so employed. The following and final, extract from the local press for Saturday 15thJanuary 1842 reported: “On Tuesday evening, shortly after 6 o’ clock, a policeman named John Dixon, while on duty in Sonning Hill Cutting (about a quarter of a mile from the scene of the late dreadful accident), and engaged in holding out his lamp on a signal to a train proceeding towards London, was struck by an engine of a down train, which passed almost at the same moment as the first train , the unfortunate man not surviving the injuries he thereby received”. As for the inquest, it was held on Wednesday afternoon at the Bull and Chequers public house at Woodley Green, about half a mile from the spot where the deceased was killed. Whilst today Woodley Green is an integral part of Woodley, the location was described at the time, as being in Sonning!

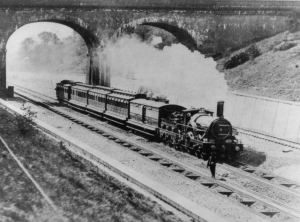

The next radical event in Sonning Cutting followed the abolition of Brunel’s 7ft ¼ broad gauge twin tracks, with four standard gauge examples. In doing so it needed a great deal of excavation work for which sturdy retaining walls were required, as well as utilising a spare approaching arch on the northern side of Bath Road bridge for one of the new lines.

Bulkeley locomotive on 20 May 1892, the final day of Broad Gauge. Photo courtesy of Paul Joyce

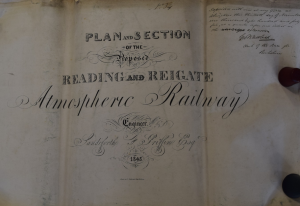

THE READING, GUILDFORD, & REIGATE, RAILWAY, THE SOUTHERN BOUNDARY

Whilst the name of Isambard Kingdom Brunel readily rolls off the tongue whenever the construction of the Great Western Railway is mentioned, sadly that of Robert Stephenson in conjunction with the Reading, Guildford & Reigate Railway that opened in 1849, is virtually unknown.

Reading and Reigate Atmospheric Railway Plan and Section of 1845. Photo courtesy of Paul Joyce

The resident engineer Alfred Giles replaced his father Francis Giles, who had been in charge until his death. Alfred was fully engaged in the planning and construction of the line almost from the outset in 1846. As for Robert, he was wisely engaged in what we would call today, a consultancy role. Fortunately for all concerned Robert Stephenson approved of all that Alfred was achieving, so much so that he told the Board of Directors that there was very little more that he could do, and that the construction of the railway was in a safe pair of hands.

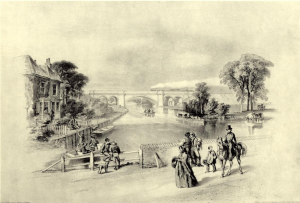

In the minutes of a (RG&RR) committee meeting held in 1847, mention was made of the line crossing the River Loddon at the rear of the public house (The George) where a market was regularly held. As for the construction of the multi arched structure it, was decided during the following year that brick would be the chosen material used.

Reading and Reigate Railway in the 1840s with the George Inn and bridge over the River Loddon. Image courtesy of Reading Borough Libraries

With construction of the line at an advanced stage in 1848, for the very first time we hear of the desire for a “halt” at Loddon Bridge. In July 1849 the line was opened throughout to Redhill. In 1852 it was taken over by the South Eastern Railway. As for passenger facilities at Loddon Bridge, no more was heard; whilst the sparsely populated south Woodley and Bulmershe districts had to wait until July 1863 before Earley station was opened.

You may well think that mention of Earley station is somewhat out of context in our study of Woodley, but the following should dispel any lingering doubts. In the Reading Standardnewspaper for 3rdFebruary 1961 it was reported that the Woodley Parish Council thought that the station should be renamed “Woodley and Earley”. It goes on to say, “A committee report, adopted at the council’s last meeting on Thursday the previous week, noted that the station, situated in the parish of Woodley, is increasingly being used by Woodley residents, and the name Earley is proving inconvenient. An approach is being made to British Railways.” Unsurprisingly in reply, the Reading Standardedition for 3rdMarch stated that British Railways had turned down Woodley Council’s request.

SKATING ON ICE

We now return to the Victorian era and Mr. Wheble’s Bulmershe Court. Within its boundary was a lake that was renowned for freezing over during those hard Victorian winters of times long past.

Whether an entrance charge was made, we will never know. Nevertheless Mr. Wheble positively encouraged the general public to come and participate in skating. Surprisingly the numbers that travelled from Reading by train to Earley were quite substantial, especially so around New Years Eve 1880 when according to a letter written to the editor of the Reading Observer, all was not as it should have been.

“Sir – Will you allow me to enter a public protest against the management which occasions such discomfort to passengers by the 1.50 train from Reading to Earley, whenever the ice bears on Mr Wheble’s lake at Bulmershe.

Although the railway officials know by experience that the train is used day by day by hundreds of skaters, and though there are two pigeon holes for the issue of tickets at Reading [SER] station, yet only one window is ever open…”

Ben Clarke’s woods were very extensive, encompassing virtually all of the land southwards from Silver Fox Crescent and Wood Way to the railway line at Earley. As for the other direction, they stretched from Drovers Way in the east, westwards to the bridleway that connected Bulmershe to Earley station.

With the exception of Loddon Bridge Road, the latter two bridleways provided the only direct connections to Earley and the Wokingham Road: the boundary being the railway line that ran from Loddon Bridge westwards to Mays Lane.

An anomaly that was to be ‘tidied up’ in a later reorganisation of the local authority boundaries, was the 1950s playing field in today’s Earley, that was originally accessed from both Hillside and Meadow Roads, to the south of Wokingham Road. Strangely, one might think, the notice boards informed all and sundry that the park was administered and maintained by the Sandford and District Council.

Today, access to Drovers Way (and Woodley) from Earley, is via a tunnel from Pond Head Lane beneath both the railway line and the A329M. Prior to construction of the motorway in the early 1970s, an unmanned level crossing had existed from the opening of the railway line in 1849. With just one property on the Woodley side, namely a small cottage, vehicular traffic over the lines was minimal to say the least. No doubt as an aid for passengers to shorten their walk to Earley Station from Woodley, a narrow footpath diverged a short distance to the north of the cottage; in doing so running diagonally in a south westerly direction to a style that provided access to a foot crossing over the lines.

Sadly in March 1940 a tragic accident occurred on the unmanned level crossing when a delivery van operated by Messrs Ferguson, wine and spirit merchants, was endeavouring to make a delivery to the cottage. Having opened the gates, the driver, John Viner, never double checked that the line was clear. By the time that he was on the first set of rails a Reading bound electric train was a mere twelve feet away!

EARLEY STATION TO LODDON BRIDGE -THE SOUTHERN BOUNDARY

Before we venture away from the location of the cottage, which today is buried beneath the motorway, mention must be made of the stream that having crossed beneath the railway, adjacent to the previously mentioned style, closely followed the diagonal foot path to Drovers Way. With a dense canopy of woodland as a backdrop, and in spring, a profusion of bright yellow, buttercup like, celandines, covering the far bank of the stream, what more could a person ask for.

As it turned out, there was still plenty more to excite any lover of the countryside. Having turned to the east the stream passed beneath a low rudimentary bridge, constructed from old railway sleepers; in doing so heading towards the distant River Loddon. There now followed a short stretch through meadow land, with the far bank in April once again covered with wild flowers, this time with a sea of white wood anemones as well as the first bluebells, before yet more pleasant woodland was traversed. Sadly today, all traces of the stream are either beneath the A329M, or beneath ground in culverts, much of which was covered during the construction of Coppice Road.

Fortunately all is not lost, as South Lake in all its beauty has survived as a public amenity, as has the adjoining High Wood. As for Ben Clarke’s splendid house, we need look no further than The Waterside public house (formerly The Thatchers) in Fairwater Drive.

THE DUNKIRK EVACUATION

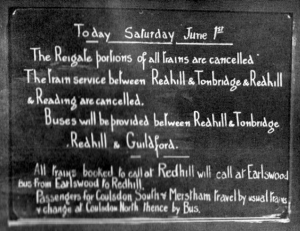

We now turn to 19th May 1940 when the first formal meeting took place to consider the evacuation of British troops from Northern France. In doing so it was agreed that the railway junction at Reading, that gave access to Wales and the West, the Midlands, and the North, would play a key role, as would the line between Redhill and Reading. In doing so, all non military traffic would cease over the latter throughout the emergency, with commandeered Maidstone & District buses acting as passenger replacements.

At a further meeting, just days away from the emergency commencing, it was agreed that 186 locomotives and their crews would be put on standby, for which the Southern Railway locomotive depot at Reading was fully committed. In addition to which the four main railway companies agreed to contribute 186 trains, each formed of ten carriages, to a common pool that would be hastily sent south and dispersed in readiness for that fateful event.

At dawn on Monday 27th May “Operation Dynamo,” as the evacuation was code named, commenced. During the following four days, virtually all of the heavily loaded evacuation trains, mainly from Dover, were sent to military camps in the South of England, including which were the huge establishments in and around Aldershot which received 60,000 men, and Bulford and Tidworth on Salisbury Plain, to name just three examples.

As for Sonning Cutting’s initial involvement, on day two, the 28th, not quite everything was destined for the military camps in the South of England, as six trains were recorded passing through, almost in convoy; having departed from Ramsgate at 3.32pm; Margate 3.54pm; Ramsgate 4.30; Sheerness 4.35pm; Ramsgate 4.50pm; and finally Sheerness once again at 5.05pm. As for their different routing, with their landing locations being nearer to the Thames and Medway estuaries than Dover etc. logic dictated that their journey towards Reading entailed heading northwards towards London, before circling around through the south western suburbs to Kensington, and finally North Pole Junction in West London, where the GWR main line to the west was joined.

Many were the trains arriving at Reading with the authorities still not having established their final destinations, all of which had to be sorted out as best as was possible in such desperate circumstances, with just aid of telephones to do so. All the way from Kent, barring a brief stop for a cup of tea and a “Wad”, it had been a case of keeping the trains moving onwards, so as not to cause congestion back down the line.

As for the line through Earley, with the garrisons to the south now virtually full to bursting point, from first thing Friday 1st until the following Tuesday, the line was to witness a non-stop procession of troop trains.

Dunkirk photo courtesy of Paul Joyce

To give an all too brief idea of the volume of traffic departing from the Channel Ports, bound for Reading and beyond, we can do no better than to look at a short sample from 1stJune, and their departure times from Kent. – 6.35am to Penally; 6.55am to Leominster; 8.00am to Brecon. 7.57am to Plymouth; 8.28am to Usk; 8.08am to Plymouth; 9.00am to Pembroke Dock; 9.18 to Portcawl; 9.18am to Abergavenny; 9.30am to Pembroke; 9.45 to Llanwit Major – all baring two examples, having emanated from Dover.

Or to put it another way, of the 565 evacuation trains that departed from Kent during the emergency, 293 came through Reading: Added to which would have been an even greater number travelling in the reverse direction, consisting of empty stock workings returning to Kent to pick up yet more men, coal trains for replenishing the locos, and much needed military supplies. Finally if all of the latter was not enough for the exhausted railwaymen to have endured, come the final day, and approximately 80,000 children, formerly having been evacuated to Kent for safety in 1939, were dispersed throughout the land, as the perceived threat of a German invasion grew.

DISASTER AT LODDON BRIDGE

Visually the railway had always been regarded as the southern boundary of Woodley, and so it remained until work on the construction of the A329M by the contractors Marples Ridgway, commenced in 1972. Completed and opened throughout in 1975, it had been delayed by the collapse of a 24 metre span at Loddon Bridge 24th October 1972, whilst concrete was being poured. Seeing the disaster unfold, it was a 999 call from a fourteen year old boy that alerted the police and set the rescue operation in motion. As for a description of the following events we can do no better than to quote the reporters from The Wokingham Times who speedily arrived on the scene.

Three Deaths & 14 Injured

“ Like so many ants, rescue workers swarm over the wreckage feverishly searching for survivors. Every now and then there is a pause as they listen for cries from the injured. But there is silence except for the drone of generators as fire engines pump out brown, murky water to reduce the level of the river. So the search continues. This was the scene on Tuesday when three men died and ten were brought out injured after being trapped in the tangled mesh of girders, rods and splintered wooden frames. …

One of the injured men, his face white, drawn and tired; his head wrapped in a swathe of bandages, his clothes covered in blood, sits in a waiting car. Shocked as she was, Mrs. Guntrip still managed to make tea for the helpers. “I’ll never forget what I saw,” she said.”

During the morning there were over 40 men working on the span, but it was lunch-time when the disaster struck and half of the men were having their break. Mr. Tom Murphy of Finchampstead, Wokingham, was near to the canteen 75 yards away. He heard the crash and turned round in time to see the span hit the water. His brother Joe was one of the men working on the other shift and was slightly injured as the scaffolding plummeted down.

As the alarm was raised at 1:15 every available ambulance in Reading was ordered to the scene. They were joined by others from Bracknell and Wokingham until 20 were ready.

In the canteen on the site, roll calls were taken. A group of men, covered in mud and grime, answered as their names were called. There were embarrassed coughs and nobody dared to look at each other as the foreman read out the names and there was no reply. A cross was put by the name and the foreman read on. …

The collapse happened when tons of liquid concrete were being poured into the bridge “false-work” – a temporary bridge of steel piles and girders. After the concrete had set, the false-work is taken down and the bridge of concrete left.

This false-work had previously been used on the west-bound bridge until the beginning of August and was due to be moved along the river to help construct the lower slip road.

PUBLIC TRANSPORT

Under the ownership of Edwin Venn – Brown, of Bell Street, Henley, Venturaintroduced a bus service between Reading and Hurst via Woodley, in May 1916. In May 1921 the service had been withdrawn, in doingso leading to The Thames Valley Traction Company [TV] serving the route.

Thames Valley traction Bristol 774 leaving Reading Station for Woodley and Wargrave. Photo courtesy of Paul Joyce

A further name to disappear was that of Povey Brothers of Sonning, following their offer of 13thMay 1926 to sell their Reading – Woodley – Sonning service. With a fee of £100, and no vehicles involved, the route was taken over by Thames Valley.

The new service from Reading encompassed Woodley, Sandford Mill and Hurst (Townsend Pond). In doing so, it was soon to receive complaints from Wokingham District Council who considered the road between Woodley and Sandford Mill unsuitable. With a width in places of no more than eleven feet, that included numerous bends around Sandford Mill, as well as numerous small bridges, the Council were concerned that the surface would soon deteriorate under the constant pounding.

Seemingly undeterred Thames Valley took little notice of the complaints and continued as before. As for the Council, they too took no further action.

A short while later a handbill was printed announcing an improved service from Monday 11thOctober for the unnumbered route that included a number of shorter distance workings between Reading and Woodley, in doing so compensating somewhat for the loss of the former Povey Brother’s services.

In 1931 Thames Valley ran an extended 1a service from Reading to Woodley that continued eastwards to Hurst, Sherlock Row, the Walthams, Cox Green and Maidenhead. Presumably the extended venture proved to be un-remunerative and subsequently curtailed, as from 1934 the 1a route to Woodley (Post office) is described as once more being extended to Hurst. Two years later a new route, the 1b commenced between Reading stations and Woodley Turn, via Sonning, to Twyford.

Come the war in 1939, and due to road closures at Woodley resulting from extensions to the airfield, the 1a service was once again curtailed; this time to operate between the airfield entrance and Reading. On a plus side the new service had a greater frequency as it attempted to cope with the 32% increase in patronage between Woodley and Reading, resulting from the growth in aircraft production there.

By 1940 the growth in bus usage to the airfield was still increasing at an incredible rate. Now instead of the pre-war services that used single deck Tilling-Stevens buses, the increased services required at least one double deck bus per journey, throughout the day, with several additional reliefs at peak times. So bad did things eventually become, that only members of the workforce with official passes to the aircraft factory were carried on certain services. As for the printed timetables from the era, they carried a notice clearly stating the new restrictions.

Following the evacuation of Dunkirk, the British Army had lost the greater part of its vehicles and armaments. To rectify the shortage virtually all bus production ceased; in doing so leading to severe shortages throughout the land. As for the Reading – Woodley services, for a period of time loaned Westcliffe-on-Sea liveried vehicles put in appearances, which being painted cream and red, be it in differing locations, complemented those of Thames Valley.